What is this Unit about?

In the Introduction, we considered the concept of strategic communication and gained familiarity with the course scenario. We also thought about our focus and scope for the project, reflecting on how we would respond to the request for proposal. Now, in Unit 1, it’s time to refine our ideas for the project, determine the rationale for and value of our project ideas, and think about how we will present them persuasively to the client in the Proposal. By the end of this Unit, you will be able to:

- Explain the purpose and nature of Proposals as a genre of professional writing;

- Demonstrate skills in assessing rhetorical context as a necessary starting point for any persuasive and strategic professional communication, especially proposals; and

- Demonstrate knowledge of basic document design principles

When you’ve completed this Unit, you will be ready to produce your Proposal.

Unit 1 Sections

- The Logic Behind Proposal Writing

- How to get People to do what you want: Tips for Persuasive Communication

Section 1: The Logic Behind Proposal Writing

Knowledge Mobilization and the Value Proposition

LESSON

At the most general level, a proposal makes an offer of something of value. In a professional context, we might:

- propose to offer our services to complete work for someone (such as persuading a prospective client that we offer the best value for money).

- propose a course of action (such as persuading our manager to invest in training).

- propose some kind of research to help with expanding knowledge and potentially to inform decision-making (such as persuading a client to fund research into a pressing social issue to inform policy decision-makers, which is our scenario for this course!)

All professional proposals require similar attention to audience identification, the development of a clear sense of rationale, and a value proposition. The proposal should offer a pursuit of action or knowledge that is clearly valuable in a well-defined context.

In the case of a research style proposal, which is our focus, we can position the proposal as an argument for specific knowledge mobilization: our project is to develop researched recommendations to inform future policy development related to social isolation and loneliness and to develop communication documents to share those researched recommendations to multiple audiences.

Defining what the proposed project will accomplish, the intended knowledge mobilization, is not the only job of a proposal. The Proposal must also convince its audience of the value of the proposed project within a social context. We need a clear sense of the why: what benefits will come from the effort and investment in this research?

Professional proposals will require a variety of distinct templates, depending on their industry and core purpose; however, we can identify essential elements of a good proposal:

- Establishes the promised goal or deliverables – What project is being proposed and what will be the goal and outcomes of that project?

- Establishes a clear purpose – What has motivated the need to propose the project?

- Establishes a clear value proposition – Why is this proposed project important currently? What will be the benefit of the promised goal or deliverables?

- Establishes a clear audience and context – Who will benefit from the proposed project? Who is the audience for the proposal itself and how can they best be persuaded to support it?

READ

| Begin by reading “Knowledge to Action Process,” “Building a Knowledge Management Plan.” https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/knowledgemanagement/chapter/introduction-to-knowledge-management-and-communications-building-a-kmb-plan/ and https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/knowledgemanagement/chapter/introduction-to-knowledge-management-and-communications-models-and-frameworks-2/ These readings help us contextualize your full course project as knowledge mobilization – you have a contribution to make to a social debate and want it to be engaged by larger communities. It’s always helpful to have an example. Now read over “The Research Policy Proposal.” This reading illustrates an example of a strategy to write a proposal for a contribution to policy debates; this one focuses on primary research where yours will be mostly secondary research, but the model is illustrative of your own project. Finally, read “Understanding Your Value Proposition.” https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/knowledgemanagement/chapter/communication-tools-and-strategies-understanding-your-value-proposition/ Here we begin to get indto the specific goal of any proposal document – establishing the value proposition. You will use the 5 questions outlined in this reading as a basis for developing your own Proposal. |

THINK & ENGAGE

| As you complete these readings, consider the following questions: Reflect on the term “knowledge mobilization.” For this course project, what kind of knowledge mobilization are you being asked to do? What is the implied purpose of the knowledge mobilization? Why would it be valuable to generate and share new knowledge and ideas on the topic of flexible work to help decision makers make social, economic and political policy? What might be the value proposition for your specific project? Who will benefit if you do your research and make recommendations? What kind of new knowledge or way of thinking do you want to research and promote? What contribution are you hoping to make? Take a few minutes to review the template for the Proposal provided in the RFP for the course project. Aim to identify the areas of the proposal template where you can highlight the value proposition of your project. |

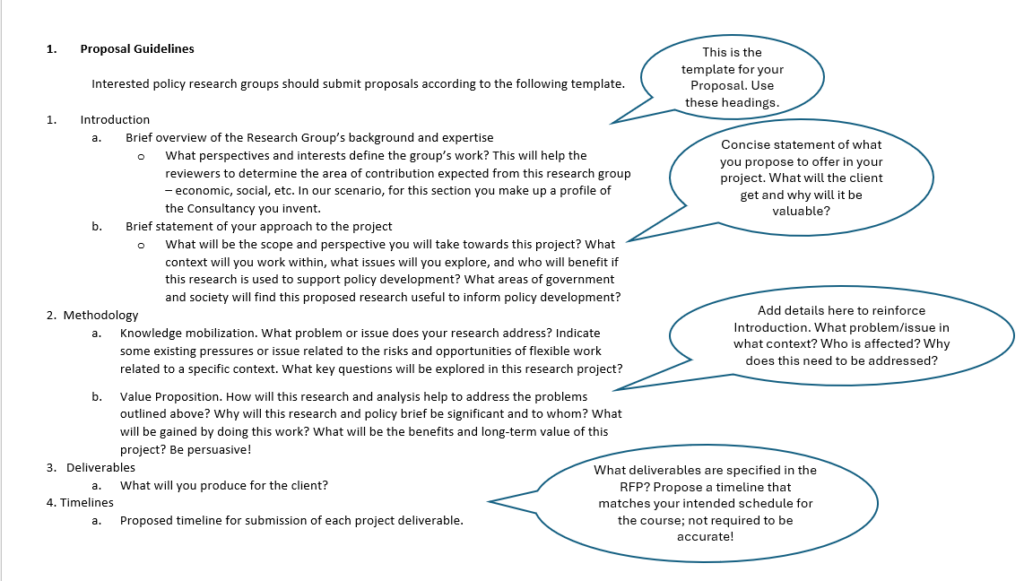

Review the Proposal Template

The template for the Proposal directs you to focus on the key elements of knowledge mobilization and value proposition. Your challenge is to define a project that expands our knowledge and action on a relevant issue that will have clear value for a specific community. Once you are familiar with the template, so you know what you need to do, it’s time to begin to think about the actual content of the project. This is in the next Lesson.

Distinguishing Proposal and Project

Writing a proposal for a project is more complex than it sometimes appears. To do it well, we must first have at least a general sense of the project we want to undertake; we can’t propose to do a project that is not at least somewhat defined, and we should know the purpose, audience, and scope of the project we want to do. The next section, below, on defining the rhetorical situation, will help with this. We may not have completed in-depth research, but we must know enough about the topic to propose an interesting approach to it.

To write a proposal, however, we also need to figure out the purpose for the proposal itself so we can position our readers to follow our logic. We need to frame our project idea within a proposal that clearly establishes the value of doing the project for a specified community.

Let’s consider this brief example of developing a Project idea and then placing it into a proposal:

Topic: Flexible Work: Risks, Opportunities and Issues.

- Focus: Career success for working caregivers and the role of accessible childcare options.

- More focus: Flexibility for caregivers to manage effective childcare within the structure of the workday could have potential economic as well as social benefits (more career success, econ benefit to employers, stable and less stressful family dynamics, see what the research might show).

Resulting Project Idea:

- Research ways in which caregivers struggle to manage childcare responsibilities within the structure of employment (select office work sector). Research resulting challenges of restrictive or inaccessible childcare options due to nature of work conditions, and what the benefits of resolving these challenges might be to develop policy recommendations.

- Purpose of the Project: to research and produce a policy brief that engages with the issue of conflict between the structure of work schedules and the demands of childcare to produce recommendations for resolution in the interests of families and the larger labour market.

- Audience: policy and change makers within industry and government areas related to economic development and child and family well-being.

Subsequent Proposal for this project:

- Purpose of the Proposal: to outline the knowledge mobilization achieved through the proposed project and to establish the value of doing the project.

- Audience: the group or organization deciding to support or fund the project being proposed.

From this example we can see the beginning idea of a Project related to the course scenario. It does not have to have all the answers, but work has been done to scope a concrete and defined focus and issue related to the general topic. We can see what issues or concerns will be explored, whose interests would be considered, and how it might connect to questions of policy development. Using this project idea, we would then move to the Proposal, to present this idea as a valuable and worthwhile endeavor.

When writing the Proposal, it’s important to distinguish between the project and the proposal itself. Consider the distinctions in these two sentences:

- “The Proposal aims to demonstrate the value of a project related to childcare accessibility.”

- “The proposed project will examine how access to flexible scheduling might reduce the challenges associated with poor childcare accessibility.”

The next sections will help develop the language skills needed for an effective and persuasive proposal.

Defining the Rhetorical Situation

LESSON

As you prepare to write the Proposal, the first step may be the most challenging. This is to figure out exactly what perspective and focus you want to take in this project. The RFP gives you several suggestions to select from, but it can be overwhelming. This Lesson is designed to help you narrow down the focus and scope of your approach to this project by selecting a particular set of interests to work within.

We don’t think and write in a bubble. Rather, we always already exist in conversation with the society and cultures around us. When we do research and absorb the news of the day, we are learning different ideas and perspectives in those conversations; and when we offer our own ideas and arguments, we are providing more perspectives back into society – participating in that conversation. And, when we do this, we are doing it from a specific perspective and framed in the interests of a specific position.

One way to define this is with the concept of “rhetorical situation:”

“The rhetorical situation involves the interplay among the speaker’s or writer’s purposes, text, audience, and academic, public, or professional context within which the communication occurs.” Topf, Mel. “Rhetoric”

Let’s first consider perspective and framing. In our course project, the general topic is Addressing Social Isolation and Loneliness. Any contributions to this general topic will be informed by the interests and perspectives taken.

For example, specific consideration of the impact social isolation and loneliness might have on newcomers to Canada would be one way to approach this. The interests and perspective of newcomers might be considered from an economic lens (exploring for example question of accessing community supports) or a health and wellness lens, exploring for example the impact of social isolation and loneliess on one’s mental health. In comparison, the question of social isolation and loneliess might raise quite different issues from the perspective of school teachers or employers looking at it through an economic lens or a technology lens.

The next thing to consider is timing and motivation. Why now? What conditions within the larger social conversation lead to the motivation or urgency to develop a position at any given moment? For example, post-pandemic conversations and debates around the nature of social isolation have been the motivation or exigence that led to the choice of topic for our Course Project. The timing or Kairos for conversations rethinking the nature of work is good now, as we collectively negotiate what a return to “normal life” might look like.

More specifically, as you select a perspective and issue for your own approach to the course project, think carefully about what kinds of issues might be urgent in the existing social conversation. For example, using our example from above, we might conclude that complicated access to community resources in a rural community is an emergent crisis for many newcomer families (exigency); given this urgent social situation (Kairos), we could define value in research into approaches to addressing social isolation and loneliness that would benefit newcomer families (perspective and lens). Taken together, these considerations form the rhetorical situation for your project.

Your goal for this Unit is to prepare a similar rhetorical situation which will become the foundation of your Proposal.

Consider how this is summarized in a passage from your readings:

“To reiterate, when you locate what you believe to be urgent for the given time, you have a rhetorical situation: you can refine your purpose, figure out who your argument impacts the most, and decide on the best type of text to reach readers who have the power to make the change you seek and under what conditions. Think of it this way: exigence and kairos are the fuel that drives our rhetorical choices forward.” (Mele, K. “Rhetorical Situation, exigence, and kairos” )

READ

| Here is an introduction to the basic terms and concept of the rhetorical situation. Read, dig in with more depth. Understanding the motivation and urgency in an existing context or social conversation is key to defining value for a proposed project. Read: “Rhetorical Situation, Exigence and Kairos” |

THINK & ENGAGE

| Audience. As we enter into social conversations and debates, we always do so from a defined perspective or set of interests and we take on a lens that shapes the way we view a situation. We need to be aware of our own perspectives as well as those of our audiences; how will others react to the perspective adopt? And how will the perspective of our audiences shape how we communicate about the issues? Exigence. The circumstances in current social practice or conversations that generate a need or gap to be addressed. A current gap in knowledge that needs to be filled or a problem in practice that needs to be fixed. If there is no exigency, no recognize gap in knowledge or problem, there will be no clear value to the proposed project or solution. Kairos. Sometimes, current situations create opportune moments to conduct research or solve problems. When it’s a timely moment to address a problem this is kairos. Rhetorical Situation. A general term to explain the coming together of perspective, audience, exigence, and Kairos. The context out of which we pursue new knowledge production. |

Section 2: Strategies for Persuasive Communication

The resources in this section help you to build skills in identifying audience need, defining the purpose for communicating, along with building some tools for persuasive writing. The skills and tips covered here will apply to all your assignments for the course. But you will have an opportunity to apply them first to the development of your proposal assignment.

Writing for your Audience – User Centred Design

Take a moment to think about how some popular advertisements match their purpose to their audience. For example, the “Hey Siri” campaigns are designed to condition consumers to use Siri on Apple devices for a range of conveniences, from trivia, to directions, to recipes. The purpose of the advertisements is to increase use of the Apple platform. But they do this through an investment in the audience’s desire for more and more convenience, showing the value proposition to the audience. It would not work if the advertisements focused on Apple’s own motivation to have consumers use their platforms to facilitate increased data collection.

Strategic writing aims to link the purpose of a communication to the needs of the audience in order to be effective in the given context.

READ

| Start with “Writing Purposefully” by Kate Mele. And then read “Writing Audience into your Text.” These readings remind us that any form of strategic writing is writing for a purpose to a specific audience. Audience and purpose need to be thought of together, as mutually informing concepts. Our purpose is shaped by the intended audience and our audience is defined by our purpose. Keep these integrated concepts to mind as you shape the persuasive message of your Proposal. Finally, a general reminder of basic principles of user-focused strategies for professional writing. “Using Rhetorical Principles to Produce Reader-centred Writing.” This excellent article should be used as a checklist for your writing in this course to ensure you are writing not for yourself, not in a bubble, but for a specific audience, to engage a specific context and bringing a specific perspective. |

Consider this example approach to the course project:

Topic idea: Debate over including childcare facilities within the workplace to enhance parental access to quality work environment.

Purpose of Project: To examine the challenges of providing childcare in the workplace and make recommendations for policies that will facilitate increase provision of childcare by employers. The project will focus on the economic benefits and so take the perspective of economic development.

Purpose of the Proposal: To demonstrate to decision makers in the context of economic development that this area of research into workplace daycare is valuable as it addresses their potential interest in economic development opportunities.

Note that if we shifted the context of the project away from economic development, towards the perspective of family health and well-being, then the argument for the value of the research would be much different as the interests of the audience would be different.

Writing to Persuade

As mentioned, a proposal is a persuasive document. A proposal must convince the reader that the plan of research is worth doing in the interests of a defined perspective and community. To do this, in addition to linking purpose and audience, as discussed above, we need to write persuasively, using specific tools of persuasion to ensure our message has credibility (ethos), appeal (pathos), and substance (logos).

READ

| Watch the TedEd video “What Aristotle and Joshua Bell can teach us about Persuasion.” Then read “The Rhetorical Triangle: Ethos, Pathos and Logos.” And one more summary of the concepts: “Logos, Ethos, Pathos.” Note the focus here is on the primacy of Logos in professional writing; but the elements of pathos and ethos are built into how the document is put together and how the story is told, as much as in the content, which tends to be dominated by strategies of logos. |

Logos:

- The proposal is structured logically and effectively with a clear purpose and objective.

- The proposal is based on relevant evidence and examples so that it is substantive and authoritative.

- The proposal is written with concrete and professional language so that it provides a substantial message.

Ethos:

- The credibility of the proposal is established with quality accurate professional writing, use of the conventions of the genre, professional level of language, use of the template and given headings.

- The credibility of the proposal is established with quality content such as research and data to secure reader trust, relevant vocabulary, and the clear sense of engagement with existing research and debate in the perspective chosen.

Pathos:

- The proposal is written with clear attention to audience needs and motivation. What problems or challenges are facing the audience? And why will this research help them?

Refresher on Principles of Document Design

The skills covered in this course are relevant across a range of disciplines and industries. Students often come into the study of strategic communication from a variety of backgrounds and interests. This section on principles of document design might be all new to you, or a refresher, depending on your background. Take time to go through the video lesson, and take notes where needed and confirm your knowledge where you can. The activity below will help you to synthesize the information from this video.

Once you have completed the Introduction and Unit 1, you have the tools you need to complete the Unit 1 Assignment: The Proposal. The instructions for the assignment are found here.